Case Study: Damage and Spray

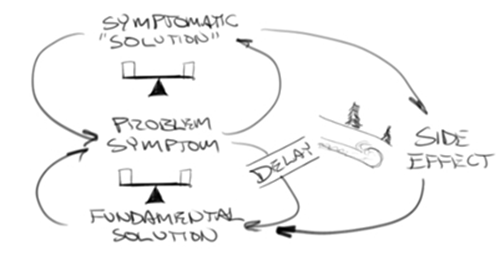

No real problem has a solution.

Why?

Because the solution to a problem changes the nature of the symptoms of the problem, not the problem itself. The real problem is hidden from sight.

If we look closely at the key elements of what happened in the example of Opportunity Contracting from the last post, we may not see the real problem. The solution did not change the nature of the problem; it only changed the symptom, compounding the problem into even more problems.

What we see is an example of the Shifting the Burden Archetype of systems thinking. In our example, the local project managers thought that replacing one contractor with another was the right solution to the problem. However, while it may have been a good temporary fix for the problem, it only fixed a symptom of a far larger problem.

Breaking It Down:

What do we know about this project?

- The customer moved the schedule of the project up, significantly.

- The engineering work was not completed when the physical part of the project started.

- Not all of the required contracting for the project was completed when the physical part of the project started.

- Manufacturing, by both the contracted suppliers and the Prime Contractor’s factories, could not accelerate schedules enough to meet the new schedule.

Any of these are root causes that increase the risk of failure, but they are still symptoms of a much larger problem. What is the larger problem? Assumptions.

Assumptions are the root cause of most failure. An assumption is nothing more than a guess. It might be an educated guess. It might be an experienced guess. But still, an assumption is a guess.

The Prime Contractor accepted the schedule change, making the assumption that it could navigate the problems that the schedule change would create. The Prime Contractor assumed that it could shift its own internal manufacturing schedule. The Prime Contractor assumed that the external suppliers would shift their manufacturing schedules to adjust to the change. The Prime Contractor assumed that it could purchase from other suppliers if the primary supplier could not meet the new schedule. The Prime Contractor assumed that it could overcome contracting difficulties with the Subs, either through change orders or by hiring replacements. The Prime Contractor assumed it could accelerate the project by bringing in more people.

Here is a specific example of how assumptions undermined the success of this project. It lists the assumptions that the procurement manager made when issuing the PSA to the new installation contractor. The procurement manager:

- Assumed that the project manager and the installer covered the entire scope of work.

- Assumed that the scope of work on file accurately represented the actual work.

- Assumed that the installation contractor had a copy of the scope of work and the related drawings and documents.

- Assumed that the subcontractor was experienced enough to ask for the documents referenced in the PSA.

My grandfather taught me a long time ago that when we make assumptions, we make asses of ourselves. Throughout my career of managing projects, it is the assumptions that have always bitten me in the ass. Competent project managers never take assumptions as fact.

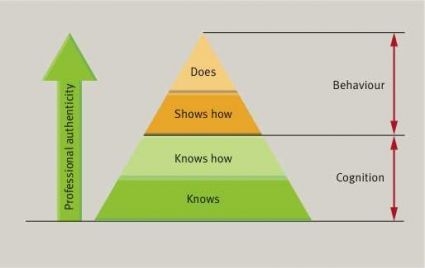

Comprehension or Competence?

The local site managers never stopped to consider whether the issue with the first installation contractor was a matter of competence or comprehension. They may have been competent to do the work, but failed to comprehend the details of the work. We will never know if that was the issue, because the Prime Contractor's management team never asked the question.

We do know, from comments made by the replacement contractor, that the incomplete engineering created a considerable amount of rework. Conveyor lines installed per the drawings, using the exact conveyor sections as defined on the drawings and in the conveyor lists, did not fit into the space. Scanning tunnels intruded into the space used by other conveyors. Conveyor sections ran off the supporting platforms into thin air. Curved sections did not fit. While these could have been errors in manufacturing or errors in engineering, they definitely were not errors in the competence or comprehension of the installation team.

We do know, from comments made by the replacement contractor, that the incomplete engineering created a considerable amount of rework. Conveyor lines installed per the drawings, using the exact conveyor sections as defined on the drawings and in the conveyor lists, did not fit into the space. Scanning tunnels intruded into the space used by other conveyors. Conveyor sections ran off the supporting platforms into thin air. Curved sections did not fit. While these could have been errors in manufacturing or errors in engineering, they definitely were not errors in the competence or comprehension of the installation team.

Imagine the friction created by the amount of rework. The subcontractor installed the conveyors per drawings and instructions. Sometimes the installation contractor could see where there was a problem and report it to site management. Sometimes the Prime Contractor’s managers would discover the issue. Sometimes the customer’s engineers found the equipment conflicts and reported them to the Prime Contractor. It did not matter how the problem was discovered; the solution always involved the Prime Contractor’s engineering group, and there was always a delay in work waiting for the solution.

While waiting for the solution from engineering, site management would assign the installation teams work out of sequence, installing the conveyors that would appear later in that system, or even switching the teams to work on a completely different system in the project. The out-of-sequence work hampered productivity. And when the solution finally appeared, productivity suffered again as the installers dismantled, modified, moved, and reinstalled the conveyors. It would have been bad enough to do the rework just once, but in several places it took three or four changes to get it right.

Switching the Deal

When the subcontractor and local managers agreed to the additional scope of work, they papered the deal as a change order. The change order was simple: 10,800 hours of additional labor to install the conveyors.

From those subcontractors' point of view, the rework just ate away at the hours in the change order. Each time there was a problem, the subcontractor site supervisor would remind the Prime Contractor's managers that the rework was chewing away at the remaining hours in the change order.

This dynamic changed a few weeks later, once the procurement manager issued a fixed price and scope PSA for the work. The contract flowed to the installation contractor's main office for signature by the owner of the company. The owner, aware that this had been a change order, was not aware of the specifics. Reviewing the PSA document, he could not find a direct reference stating that the PSA had replaced the change order. He also did not understand that the scope of work had changed from a simple bucket of additional hours to a specific scope of work, because the scope was not part of the contract itself, but was only referenced in an appendix of the agreement.

When the owner of the subcontracting companies signed the PSA, he signed an incomplete document. One could argue that signing an incomplete contract was a stupid act, which is exactly the argument the Prime Contractor would make later in the project, and in the course of the subsequent litigation. One could argue that the subcontractor was stupid to assume that the Prime Contractor would act in an ethical manner by making it clear in the actual contractual document that the scope had changed.

While the action of the Prime Contractor may have been legal, changing the scope of the agreement without making it clear to all the parties was clearly unethical.

It still gets worse.

Note: Just as a reminder given the nature of this series, I am a logistician and IANAL (I am not a lawyer).