Sackcloth Contracts

The contracting behind modern, integrated material handling systems is becoming as complex as the systems themselves. Perhaps the contracting is becoming too complex for the underlying systems. This complexity may be a sign that the material handling industry is maturing, or it may be a sign that companies are attempting to avoid risk by assigning that risk contractually to the lower levels of the industry.

The complexity of contracting may be creating mischief as much as it is helping to mitigate risk. Contracting, done right, goes a long way in mitigating risk. However, even with the right contracts in place, poor management of a project by a prime contractor can create incredible losses for subcontractors if the prime uses the contract as a club to bludgeon and intimidate the subcontractor into covering for the deficiencies of the prime.

You can dress a supermodel in sackcloth, and it may work, or it may not. This photo is an example of how good a sackcloth dress can look … or not. Decorative detail, cut, and some accessories can make the old sack work. While the effect is cute, however, is the decorated sack of a dress something that you would expect to see at a holiday party?

You can dress a supermodel in sackcloth, and it may work, or it may not. This photo is an example of how good a sackcloth dress can look … or not. Decorative detail, cut, and some accessories can make the old sack work. While the effect is cute, however, is the decorated sack of a dress something that you would expect to see at a holiday party?

The same idea applies to using a contracting structure designed for a specific industry and applying it to another. It may work, or it may not. Moreover, to make the contract structure that works well for one intended industry work well for another may require modification beyond reason, and perhaps pushes the culture of the target industry too far. Culture matters in an industry as much as it does in a country, or in a company. As the saying goes, culture can eat strategy for lunch. The culture of an industry can undermine the most determined effort to improve behavior with contracts.

No Man An Island, No Link a Supply Chain

No company has a 100 percent vertically integrated supply chain. A supply chain will consist of many different business entities engaged in the process of moving, converting, transporting, and selling material: mines, mills, factories, ships, trucks, warehouses, stores, all owned by different companies, each constituting a vital part of the supply chain for a specific product.

Likewise, no construction project is 100 percent vertically integrated by the same company. Real estate brokers, developers, architects, engineers, and myriad construction trade companies all make up vital parts of the supply chain needed to erect a building.

It should come as no surprise that complex, automated material handling systems are never 100 percent vertically integrated. This has not always been true. The history behind the development of integrated material handling systems shapes the sale, design, construction, and implementation of integrated systems today. While we may think that the material handling industry has been around for a long time, the notion of blending discrete pieces of equipment into an integrated system is rather young.

The material handling systems we find in modern distribution centers today are integrated complexities. The typical automated system may integrate equipment manufactured by over 100 different companies, and involve the installation effort of just as many different business entities. Just as the construction of the industrial building that houses a modern distribution center is a complex project involving as many as 50 different trades, the integrated material handling system inside that building is a complex project involving just as many trades.

Large construction projects are complex integrations of different materials and trades focused on manufacturing a building. A modern construction project involves multiple layers of contractors and suppliers, the general contractor controlling the orchestration, scheduling, and payment of hundreds of subcontractors. The entire process depends on the strength of the contractual documents used to define the business relationships. The building owner will have a contract with the general contractor. The building owner will also have a contract with the architect. The architect will have contracts with various companies that provide specialized services, including civil, structural, and electrical engineering, landscape design, and code compliance. The general contractor will have contracts with various companies that provide other specialized services — framing carpenters, concrete companies, electrical, plumbing, and HVAC contractors.

As material handling systems become more complex, the same business relationship structure that we see in building construction appears for these systems. A modern, integrated material handling system project involves multiple layers of contractors and suppliers. Does it make sense for equipment integration companies to build contracting structures as found in construction? Could it be as simple as replacing the word General with Prime contractor, leaving the rest of the contracting process unchanged? Or is the nature of material handling equipment systems more complicated, making it necessary to look elsewhere for other contracting models?

Maybe it is that easy, but there may be unintended consequences. We should look at the history of the material handling industry and consider the complications.

Early Material Handling Integration

While building construction contracting has existed for several centuries, making it a mature process with many legal standards in place, material handling systems integration is still developing, and some of the legal aspects are vastly different.

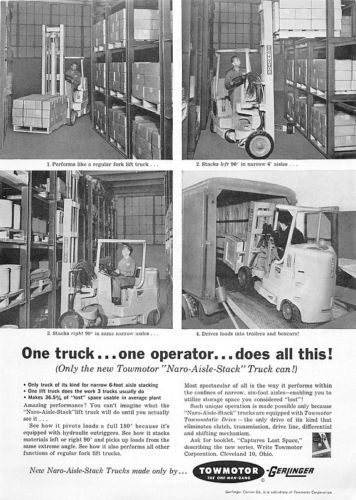

In the early days of 20th century American warehouse development, the warehouse owner developed the in-house skills to engineer and manage the construction and startup of the operation. Many of the tools we now see in material handling really came about after World War II. Before the invention of the forklift by The Towmotor Corporation in 1933, warehouses used a combination of bulk stacking on the floor using hand carts and trailers, and shelving with ladders. Most modern warehouses built before 1950 looked like factories: heavy, reinforced-concrete buildings of multiple stories, about 16 feet clear between the floor and the ceiling.

Conveyors existed before World War II, but with limited automation. The Montgomery Ward Company used conveyors in its distribution centers, first employing package conveyors in 1905 (read more about that history here). Early automation used conveyor boys — teenaged boys who read the labels and tags on boxes and cartons and then moved levers that pushed the cartons off the conveyor belt. Later the levers actuated air logic circuits that engaged and disengaged the belts, starting and stopping the lines, or flipping diverters that pushed the boxes.

The introduction of the pallet and the towmotor fork lift changed the design of the warehouse. No longer restricted to how high a man could lift a crate, stacking heights increased. Bulk stacking works well when everything in the stack is the same thing, but bulk stacking creates problems when the contents of the crates are different. With a towmotor forklift, heavy-duty shelving could support pallets, and pallet racks started to appear.

All these innovations came from a combination of clever end users who developed new methods of using available equipment, and manufacturers who saw the way the innovative engineers at the end-user companies had modified their equipment. The leaders in the industry were the big consumer goods manufacturers (General Mills, Anheuser Busch, and General Electric), the big retail players (Ward, Sears, Penny's), and the material handling equipment manufacturers. In some cases, middle-tier end users became innovators, devising new applications for existing equipment.

The common thread in all this development is how engineers and managers in the factories and warehouses drove the innovation. People inside the end-user facilities developed the plans, engaged in the construction, purchased the equipment, and integrated the systems used in the plant. Until the 1960s the engineering happened in-house.

Note: Just as a reminder given the nature of this series, I am a logistician and IANAL (I am not a lawyer).