Evolution to Outsourced Design

The development of contracting practices for material handling projects evolved with the development of the industry, and the complexity of the equipment and systems. To understand where the industry's contracting practices are today, it helps to understand the industry’s past, and the problems created along the way.

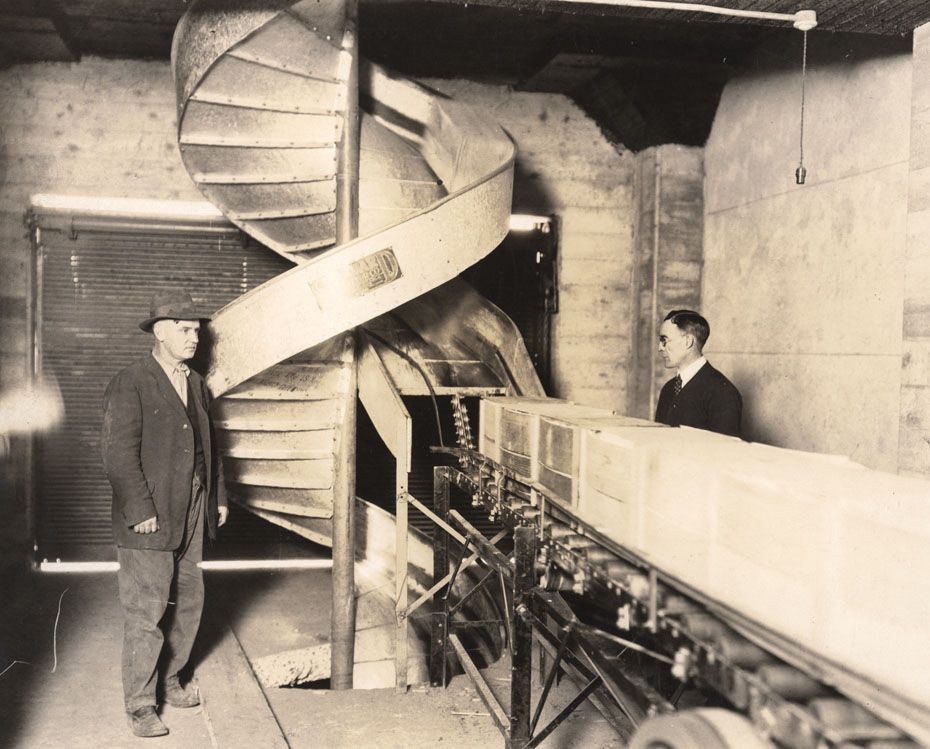

In the early days of modern material handling systems, clever engineers and operators in the end-user enterprises did most of the innovative application work. These trendsetters looked at the equipment catalogs and talked to their local equipment dealers to develop new ways to solve old problems in their facilities. These internal engineers bought the component equipment, sometimes using a simple and informal Bill of Sale model, sometimes using the more formal Purchase Order model. In either case, the buyers took on the responsibility of engineering, installing, and integrating the equipment into their operations.

In the early days of modern material handling systems, clever engineers and operators in the end-user enterprises did most of the innovative application work. These trendsetters looked at the equipment catalogs and talked to their local equipment dealers to develop new ways to solve old problems in their facilities. These internal engineers bought the component equipment, sometimes using a simple and informal Bill of Sale model, sometimes using the more formal Purchase Order model. In either case, the buyers took on the responsibility of engineering, installing, and integrating the equipment into their operations.

The Dealership Business Model

The earliest form of local sourcing for material handling equipment was the local industrial truck dealer. In the 1950s there were two types of industrial trucks: tow tractors that pulled carts, and counterbalanced forklift trucks. The major forklift manufacturers during the time period—Towmotor, Clark, Yale, and Hyster—developed the same distribution model as the automotive industry: the manufacturers made the trucks, and localized dealers provided the sales and service for the trucks.

The forklift became a productivity powerhouse as the post-war economies of the US and Europe exploded. Forklifts became the new tools for loading and unloading train cars, trucks, and ships. The modest machine was used by the US military in WWII, and its utility expanded quickly. More manufacturers jumped into the arena, and more local companies started up to provide sales and service for the growing material handling equipment industry.

Forklift dealers quickly realized that once they sold a forklift truck to a warehouse, the only future revenue would come from parts and service. These dealers needed to provide more service and sell more equipment to their customers, so they started to add allied brands to expand their offerings. These products included dock plates, battery chargers, pallet racks, and shelving. As more warehouse operations began to add conveyors, some dealers expanded their services to include simplified conveyor systems.

The most lucrative allied product for a dealer to add in the 1950s was the pallet rack. Unarco was one of the first large-scale manufacturers of pallet racks when it introduced the Sturdi-Bilt line in the 1950s. The new lifting technology of forklift trucks, the widespread adoption of wood pallets, and the introduction of Unarco’s Sturdi-Bilt pallet rack influenced the construction of new warehouse buildings in the form of the big-box structures we see today, increasing the clear height of the buildings to about 24 feet.

The end-user trend setters of the industry continued to develop new applications in-house. To help market the growth of the industry, trade magazines like Modern Material Handling printed application stories aimed at warehouse operators, which appeared in the editorial copy alongside advertisements for the same equipment. New potential end-users saw the articles about the new equipment and wanted to implement these new ideas in order to improve their productivity. In 2015, both Modern Material Handling magazine and the Material Handling Industry trade group, MHI, celebrate their 70th anniversaries, which indicates how the industry started to gain prominence in the 1950s.

Central Engineering Support Appears

In these early days of factory-supported dealers, a division of services appeared. While conveyor systems involved two different unionized and licensed trade skills—millwrights and electricians—pallet rack installation proved to be an easy expansion business. Dealers soon created their own layout design and sales teams, backed with internal and external erection teams. As demand grew for the storage racking systems, independent contractors started to fill the gap. Before the age of the steel pallet storage rack, carpenters built wooden storage systems. In the 1950s, steel quickly replaced wood for pallet rack construction, eliminating one form of work for carpenters. However, the housing boom of the era kept the carpenters busy enough to leave room for the growing industry of specialized rack installation.

While the forklift dealers understood how to sell and service forklifts, installing pallet rack and conveyor systems became a greater challenge. Some dealers kept it simple, keeping simple projects in-house. A few dealers trained their maintenance staffs to install simple pallet rack and conveyor systems. However, warehouse operators wanted sophisticated solutions that worked, requiring a level of service beyond what the forklift dealer could provide.

While the forklift dealers understood how to sell and service forklifts, installing pallet rack and conveyor systems became a greater challenge. Some dealers kept it simple, keeping simple projects in-house. A few dealers trained their maintenance staffs to install simple pallet rack and conveyor systems. However, warehouse operators wanted sophisticated solutions that worked, requiring a level of service beyond what the forklift dealer could provide.

Conveyors proved too complex for many of the new customers to design, and the forklift dealers found the design and engineering work beyond their scope of expertise. The conveyor manufacturers, eager to build business volume to keep business flowing through the factories, supported dealers with central engineering departments. The larger conveyor manufacturers developed central engineering departments to support the local dealer network. Companies like Rapistan, Buschman, Alvey, Litton, and Mathews created central application engineering departments that supported the sales engineering for the local dealers. The larger rack manufacturers like Unarco and Frazier likewise created central estimating and application engineering departments to assist dealers in creating more revenue. When a customer project was beyond the capability of the dealer staff, the dealer contacted the manufacturer's central engineering group, who provided the engineering and project management for the project. The dealer sold the project and collected a commission, but the manufacturer actually engineered and built the solution.

The Purchase Order became the primary contracting model. Purchasing managers in the buying organizations, with input from the end users, developed rough specifications of the equipment needs, and then invited companies to bid on the business. Sometimes they awarded the business on a no-bid basis, turning to suppliers, mostly dealers, with whom they had an ongoing business relationship. Looked upon as a simple “turnkey” process, the Purchase Order model defined the basic business terms and technical specifications, often referring to the quote provided by the supplier as the sole technical and pricing document for the transaction.

Consultants Focused on Planning

As demand for more sophisticated material handling systems grew, a new business model appeared in the market place, the Material Handling Consultant.

![richard_muther[1].jpg](/application/files/8914/9987/8456/richard_muther1.jpg) As companies sought out new ways to improve manufacturing productivity, they stared to focus on the equipment and machines, turning first to internal industrial engineers for design and implementation, then to outside consulting industrial engineers. The outside consultants and their firms, like Richard Muther, Irving Footlik, and a few others, started building practices that focused on planning and layout activities, developing new processes, and designing the physical flow of materials through a facility. While these firms did

As companies sought out new ways to improve manufacturing productivity, they stared to focus on the equipment and machines, turning first to internal industrial engineers for design and implementation, then to outside consulting industrial engineers. The outside consultants and their firms, like Richard Muther, Irving Footlik, and a few others, started building practices that focused on planning and layout activities, developing new processes, and designing the physical flow of materials through a facility. While these firms did  design the layout of the equipment in a facility, that was just a part of the overall project. The material handling consultants, working for the end-user clients, shaped the construction of buildings and introduced the use of computers in materials management and handling, integrating business processes with physical processes. The role was more than just material handling; these consultants advised their clients in the art and science of materials management.

design the layout of the equipment in a facility, that was just a part of the overall project. The material handling consultants, working for the end-user clients, shaped the construction of buildings and introduced the use of computers in materials management and handling, integrating business processes with physical processes. The role was more than just material handling; these consultants advised their clients in the art and science of materials management.

The leading consulting firms were all professional engineering firms led by licensed professional engineers, mainly industrial engineers by training. Following the example of Fredrick Taylor, John and Lilian Gilbreth, Henry Gantt, and Henri Fayol, these consultants focused on the factory's desired outcomes, and the processes and relationships between processes dictated the function and flow of materials. Planning became only one part of the offering, as more engineering firms formed to compete with the leaders, providing more of the functional and detail design engineering.

By the 1980s the major material handling engineering firms provided much more than just planning, offering their clients “start to finish” service that included distribution network analysis, network planning, facility conceptual design, engineered design, equipment specification development, bidding document creation, bid reviews, and on-site supervision of equipment installation, all under the watchful eye of the consultant’s project management team.

The leading consulting firms were professional firms, since the principals and many of the associates were licensed professional engineers. Like other professionals such as attorneys and accountants, the consulting engineers contracted to their clients under a defined scope of work, often under time and material terms. The contract structures used a phased approach to define the scope of a project: the first phase was the planning, the second phase was the engineering, and the third phase was installation.

In the 1980s, it was typical for fees and expenses on a three-phase project to total up to $500,000 over a period of years. Complex planning projects involving multiple locations could cost $1 million just for Phase 1. The high fees attracted competition from other consulting firms looking to broaden their base, so firms like Anderson Consulting, Lockwood Greene, and Touche Ross either bought existing Material Handling Consulting firms or created their own practices in an effort to increase their revenue from existing clients.

These newcomers pressured the existing consultants, offering what appeared to be identical services. In reality, their cheaper, fixed-price deals were not as comprehensive in detail or quality as those offered by the engineering firms because the consultants in these competing firms were not licensed engineers, but often just employees with some business consulting experience.

Note: Just as a reminder given the nature of this series, I am a logistician and IANAL (I am not a lawyer).