A Place Called ba

Traditional twentieth-century management typically focused on three resources, land, capital, and labor. In the late 1950s Peter Drucker started to recognize knowledge as a resource, and on the growing breed of workers who focused on the development of knowledge, whom Drucker dubbed “knowledge workers.” The notion of knowledge as a resource was slow to catch on, but it grew during the second half of the twentieth century. Even as the theory and practice of knowledge management sprang forth, and serious academics began to study the art of creating knowledge, companies continued to struggle with the notion of knowledge creation. They still struggle with it today.

Traditional twentieth-century management typically focused on three resources, land, capital, and labor. In the late 1950s Peter Drucker started to recognize knowledge as a resource, and on the growing breed of workers who focused on the development of knowledge, whom Drucker dubbed “knowledge workers.” The notion of knowledge as a resource was slow to catch on, but it grew during the second half of the twentieth century. Even as the theory and practice of knowledge management sprang forth, and serious academics began to study the art of creating knowledge, companies continued to struggle with the notion of knowledge creation. They still struggle with it today.

Businesses have serious difficulty understanding the knowledge resource. Many companies lack an understanding of what it takes to create a company that can thrive in a knowledge-based economy. Could it be that business leaders do not understand knowledge itself, let alone how to create knowledge?

Research and development can be a source of knowledge creation, but it is not the only source. The opportunity for knowledge creation exists in any organization. Knowledge scales, and is just as much at home on the shop floor, on the sales floor, or on the warehouse floor as it is in the lab or the executive suite.

Information Is Not Knowledge, so IT Investment Is Not Knowledge Investment

Business leaders invested heavily in information technology in an effort to create knowledge. Information technology opens the door for efficient storage transfer and use of information. Technology allows the collection, tabulation and processing of data, opening the door for the use of the term, information management. By making those large investments business leaders believed they were funding knowledge creation. But information is not knowledge, and many executives were disappointed by investments in information technology that failed to create knowledge.

What does knowledge creation require? While data and information are important in the creation of knowledge, neither data nor information creates knowledge spontaneously. There is a missing element, a missing activity, that catalyzes information into knowledge.

What Is Knowledge?

The dictionary definition of knowledge is lacking.

knowl·edge (from Webster’s)

Noun:

⦁ Information and skills acquired through experience or education; the theoretical or practical understanding of a subject.

⦁ What is known in a particular field or in total; facts and information.

Even among philosophers, there is no clear, single definition of knowledge. It is almost an “I know it when I see it” kind of thing. It is abstract, a thing that you cannot touch, taste, hear, or see. But you can feel it, you can recognize it. Knowledge can include information, facts, or descriptions. Knowledge can be the skills you learn through experience. Knowledge can be formal or informal, systematic or random.

Knowledge can be the implicit practical application of information just as much as it can be the explicit theoretical understanding of a subject area. Plato called knowledge a justified true belief.

While the word Knowledge itself defies a definitive definition, we can outline our cognitive understanding of the components and attributes of knowledge, how we will discuss knowledge here, and how many of the world’s greatest thinkers defined these attributes:

⦁ The genesis of knowledge is a problem, a conflict in our sphere of influence that we perceive needs resolution. In marketing, this is the “need in the market to be filled,” or in math, “solve for x.”

⦁ Knowledge is an organized structure or pattern of information. We gather facts from research of data, observation of events, and reading of the thinking of others. We then organize that information into patterns organized for our individual understanding. The pattern can be confusing and meaningless to others, but makes perfect sense to the individual.

⦁ Knowledge has stamina; it tends to be long-lasting. We gather knowledge over time.

⦁ Knowledge is relatively meaningful to specific individuals or groups. Knowledge about steam engines is worthless to fashion designers. Our culture values specialized knowledge and discounts broad knowledge. But many of the greatest thinkers of the modern age were renaissance men, people who possessed many talents and many areas of expertise.

⦁ Finally, knowledge comes through both introspection and experience. The ability to reason gives us the tools to consider different options—and the potential outcomes of each option. Experience guides our reasoning. Experience can be our own personal practical application, the direct observation of the practical application of others, or the study of the recording of others’ efforts. Experience can be transferred, with potentially less impact on the quality or depth of knowledge.

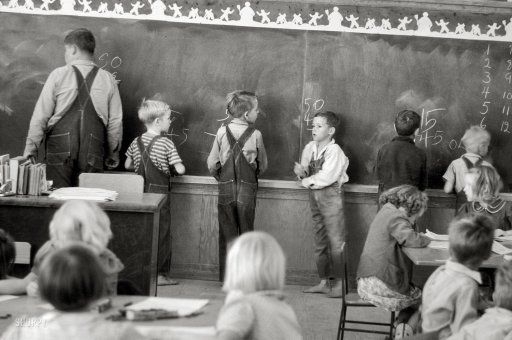

Knowledge is the creation of thought. While we can train children with information, that information does not become knowledge until they think about the information and apply it in a practical sense. Math is an example: we do not really learn math until we apply it, until we do the work. In teaching math, the teacher takes tacit knowledge and imparts it to the student. The best teachers work with examples, encouraging the students to apply the theory they have learned to the practice of solving problems on the board. The student, living the explicit experience of working the problem, turns the explicit information into skill, and into internal tacit knowledge. The practical application of the new tacit knowledge tests and validates the knowledge, exposing the next level of knowledge opportunity, and the continuous loop of knowledge creation continues.

What Is More Important for Knowledge Creation: People, Place or Space?

Creating knowledge is a complex process requiring the interaction of human beings who take internalized tacit knowledge, communicated in personal levels, discussed, argued, reasoned, until it comes explicit within the organization. It still is not knowledge until it has successfully been employed in a practical application and validated. Only when the knowledge has been practically applied is the feedback complete.

Knowledge becomes a human activity, and as such, we cannot separate the creation of knowledge from the understanding of how humans think and feel. Through the application of thoughts, ideas, hunches, and dreams we create knowledge. This becomes a subjective process filled with human instinct and emotion, which is amplified through the use of computers and other information technology.

Knowledge is not static or unmoving like a rock. Knowledge is the product of energetic, ever-changing interaction between people. While many believe that the great philosophers and thinkers in history created knowledge alone, the truth is that they benefited from human contact. Aristotle, Plato, da Vinci, Descartes, Rousseau—all these great thinkers benefited from their human interactions. Yes, they wrote and pondered their deep thoughts. They also discussed these deep thoughts with the contemporaries of their time, over a glass a wine, a cup of tea, or dinner. In these discussions and interactions the great philosophers expressed their tacit knowledge to others, and in the process externalized their thinking. By talking out their ideas, their knowledge moved from implicit to explicit. Only through the effort of moving knowledge from the tacit to explicit state did their ideas see the light of day and breathe the fresh air, taking root in the thinking of other people.

Creating Place and Space for Creating Knowledge

Businesses that successfully capture the art of creating knowledge grasp that knowledge and its management is really an accumulation of value judgments. Ethics and aesthetics dominate in the judgment. It changes the questions that companies must answer, from "How much should we make?" into questions that reflect more meaning, such as "What should we make and why should we make it?" Knowledge-creating firms are constantly generating additional value by asking and answering, "Why do we exist?" on a daily basis. Companies that create knowledge ask the most important question, "What is good?"

Business leaders who continue to ask the question, “What is good” begin to understand that that there is no single correct answer. Just as the knowledge itself defies simple definition, so does the quest for “What is good?”

Next: Groupthink and the Power of the Individual Effort

Finding a place called ba Part 2 – Groupthink and the power of the individual effort

by David Schneider

If knowledge creation is a product of both internal thought and social interaction, the notion of balance comes into question. How much internal individual effort, and how much social interaction, and how do you strike the proper balance?

Ikujiro Nonaka touches on this subject in his groundbreaking article “A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation,” published in the February 1994 edition of Organizational Science.

Nonaka starts with the work of Michael Polanyi, who in 1966 wrote, “We can know more than we tell,” when he classified human knowledge into two categories:

Following Nonaka’s use of Polanyi’s thinking, individuals create knowledge on the fundamental level. Without individuals, an organization cannot create knowledge. To Nonaka, the purpose of an organization is to support the creative individuals, providing the context for those individuals to create knowledge. Nonaka's point is that organizations must create processes that help amplify the knowledge created by individuals, and that the role of the organization is to help build a knowledge network, connecting individuals to the distribution of knowledge.

Organizations consist of both formal and informal structures. The organization chart of any company is a symbolic representation of the formal structure within. Hidden behind that organization chart is the shadow organization of leadership and connection. If you chart out the hidden connections in the shadows you will find an amazing set of degrees of separation based on the social needs of the individuals, and the operational needs of the organization. Rarely do the actual communications connections between a company and its suppliers, its customers, or its service providers mimic the official organization chart. Dig below the surface, and a completely different spiderweb of direct communication channels exists.

Team and individual

There is an argument that no great achievement is the accomplishment of a single individual. Sports analogies abound in management literature, supporting the argument that great things only occur when teamwork occurs. Consider the work of Nonaka, and how many of his writings are the product of collaborative work with other researchers and philosophers studying the art and science of knowledge creation. While Nonaka collaborates, it is clear in his writing that he values his own individual effort as much as the effort of any of his collaborators. While Nonaka may not have created his seminal writing about knowledge creation without collaborative help, it is equally true that if Nonaka had not engaged in the enterprise we would not have the value of his writings today.

Simply said, if Nonaka the individual had not invested his time and effort in thinking and writing on the subject of knowledge creation, we would not have the depth of material to study and learn. The same would be true if Nonaka had chosen not to collaborate with his peers—the quality and power of his research would not be the same without the knowledge that he developed working with others.

In a New York Times Op-Ed for the introduction of her new book, QUIET: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, author and researcher Susan Cain proposes that the most creative action comes from the quiet moments, that the modern age of team thinking and Groupthink is not conducive to the creative processes.

“The New Groupthink has overtaken our workplaces, our schools, and our religious institutions. Virtually all American workers now spend time on teams, and some 70 percent inhabit open-plan offices in which no one has ‘a room of one’s own,’” says Ms. Cain. “Our schools have also been transformed by the New Groupthink. Today, elementary school classrooms are commonly arranged in pods of desks, the better to foster group learning. Even subjects like math and creative writing are often taught as committee projects.”

The pendulum swings both ways when it comes to developing knowledge. It requires both individual effort and socialization for the development of knowledge to be complete. Organizations cannot force the creation of knowledge; they can only create settings and environments that are conducive to it, that allow individuals to commit to knowledge creation and allow the gathering of individuals to interact.

Individual commitment

The first step in knowledge creation requires an individual commitment. Nonaka highlights three basic factors that facilitate individual commitment within the organization:

⦁ Intention is an action-oriented concept, where the individual has an attitude to engage and intentionally sets about to gain knowledge. People must be motivated to seek out answers; they must be conscious of something in order to be able grasp the meaning of information. This helps the individual frame of value judgment.

⦁ Autonomy can be applied at the individual, group, and organizational levels, but in most cases, the motivation starts with the individual. Allowing people to act autonomously an organization increases the possibility of introducing new, unexpected opportunities. Organizations that embrace autonomy are more likely to maintain greater flexibility in acquiring, relating, and interpreting information. Autonomy widens the possibility that individuals will motivate themselves to form new knowledge.

⦁ Fluctuation comes from the continuous interaction of the individual with the external world. Chaos word stress can generate new patterns of interaction between individuals and the environment. It takes a periodic breakdown in human perception, and interruption of the individual’s actual comfortable "state of being," where an individual questions the value habits and routine tools. When people face this contradiction, they have an opportunity to reconsider their fundamental thinking and perspectives.

External forces, from the culture of the organization or from different cultures outside the organization, create opportunities of impact that create continuous interaction between the individual and the world. This tension inspires and motivates the individual to seek out new knowledge, test parameters, and look to their cultural peers for advice and motivation.

Superior knowledge creation requires human interaction.