I’m not talking about learning. Knowledge is more than just learning. You can learn about a subject in a classroom or from a book. But that is not knowledge. From a class or a book you learn about a subject, but at that point the learning is just theory. That you know about the subject is a theory, in that you should know the subject, but that you have not proven that you really know the subject.

Only through practice does what you learn become knowledge.

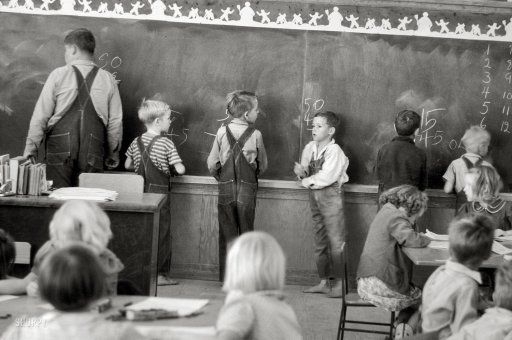

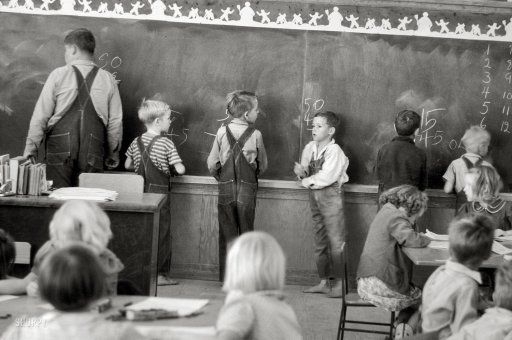

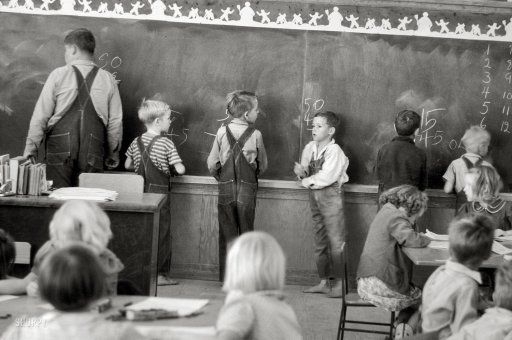

Knowledge is the creation of thought. While we can train children with information, that information does not become knowledge until they think about the information and apply it in a practical sense. Math is an example of this; we do not really learn math until we apply it, until we do the work. In teaching math, the teacher takes their tacit knowledge and externalizes it, passing it to the student. The best teachers work with examples, involving students in an explicit exercise that teaches them to apply the theory to solve problems on the board. The student, living the explicit experience of working the problem, turns the explicit information into skill, and into internal tacit knowledge. The practical application of the new tacit knowledge tests and validates the knowledge, exposing the next level of knowledge opportunity, and the continuous loop of knowledge creation continues.

I believe that one of the jobs of a good leader is to lead an organization on a journey where everyone in the enterprise creates knowledge. I believe that knowledge is a product. Any company or organization should create knowledge as part of the everyday actions of business. Sadly, it appears that not all business leaders share my belief. Oh, they will support training, and spend money to send people to training classes. But training is not knowledge creation. Training is simply the exercise of teaching somebody to follow a prescribed set of instructions to complete a task. If knowledge emerges from a training class, it is an accident.

A Historical Misunderstanding?

Traditional management typically focuses on three resources: land, capital, and labor. In the late 1950s, Peter Drucker recognized knowledge as a resource, writing about the growing breed of workers focused on the development of knowledge. Drucker dubbed these employees "knowledge workers," introducing the notion of knowledge as a resource, a notion that caught on slowly and grew in the second half of the 20th century. Even as the theory and practice of knowledge management sprang forth and serious academics began to study the art of creating knowledge, companies continued to struggle with the notion of knowledge creation.

Businesses today have a serious difficulty understanding the knowledge resource. Many companies do not understand what it takes to create a company that can thrive in a knowledge-based economy. Could it be that business leaders do not understand knowledge itself, let alone how to create knowledge?

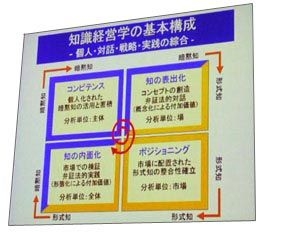

Creating knowledge is a complex process requiring the interaction of people to convert internalized tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge. People have to interact, talk, argue, just to get knowledge to move from tacit to explicit. This happens in almost any organization, by accident, or on purpose when two people make a conscience decision to work together to solve a problem.

Even when that happens, it is still not knowledge until successfully employed in a practical application and proven to work, or not work. The application validates the knowledge, demonstrating that it is correct. Only when practically applied with feedback to the people is the knowledge creation process complete.

Businesses that successfully capture the art of creating knowledge grasp that knowledge is really an accumulation of value judgments. Ethics and aesthetics dominate the judgment. It changes the questions that companies must answer, such as, "How much should we make?" into questions that reflect more meaning, such as, "What should we make and why should we make it?" Knowledge-creating organizations constantly generate additional value for themselves and for the world by asking and answering the question, "Why do we exist?" on a daily basis.

Companies that create knowledge ask the most important question: "What is good?" Business leaders who continue to ask the question, “What is good?” begin to understand that that there is no single correct answer. Just as the knowledge itself defies simple definition, so does the quest for what is good.

We all can build knowledge-creating organizations. It first starts with two people making the decision to talk about a problem, to examine, question, challenge, willing to try something new and see if it works or fails. This is a process. The following articles explore that process. This is heady stuff; these are things that you may not have invested much time thinking about. However, the articles and stories that follow help illustrate how this works.

Articles in This Series

Articles in This Series

How Does Your Organization Learn?

Perhaps the real question is, “How does your organization create knowledge?”

As Peter Drucker hit his stride in writing about business, he described a new kind of work, highlighting a fundamental fallacy in management. He wrote about a new kind of worker he dubbed the knowledge worker. The fallacy he exposed was the idea that there is one right way to manage people. Read More

Training = Programming

I have been thing a lot about the issue of training lately. Training is necessary but is insufficient. Training is necessary to program people to execute tasks following a specific process. Training is not teaching. Training covers the micro level — what to do. Read More

What is the Value of College?

Our market research last year yielded an interesting data point: over 80% of US-based supply-chain managers do not have a college degree. We were surprised at first…but after some reflection we stopped being surprised. Read More

A Hunger for Supply Chain and Logistics Knowledge

People in the supply chain and logistics industry are hungry for knowledge in the supply chain and logistics fields. How do I know? As of August 15, 2011, there were over 8,000 supply chain, logistics, transportation and warehousing groups on LinkedIn. Read More

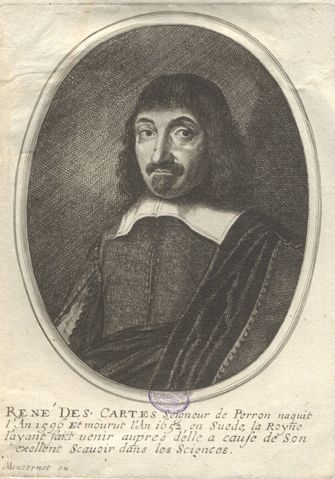

A Place Called ba: Rene Descartes and Ikujiro Nonaka Meet, Part 1

In 1637, Rene Descartes published his autobiographical work, "Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One's Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences," better known by its shorter title, "Discourse on the Method." Read More

The Complex, Context and Cognitive Gaps

That is not an easy question to answer. We may be able to define what a simple supply chain looks like, but we have some difficulty with an example. Read More

Healthy Fields

That is one of the biggest observations from my 2014 summer research trip. Lush fields of tall corn and soybeans blanketed Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa. A milder summer with good rains after a wet winter has set the table for what looked to be a significant harvest that year. Read More

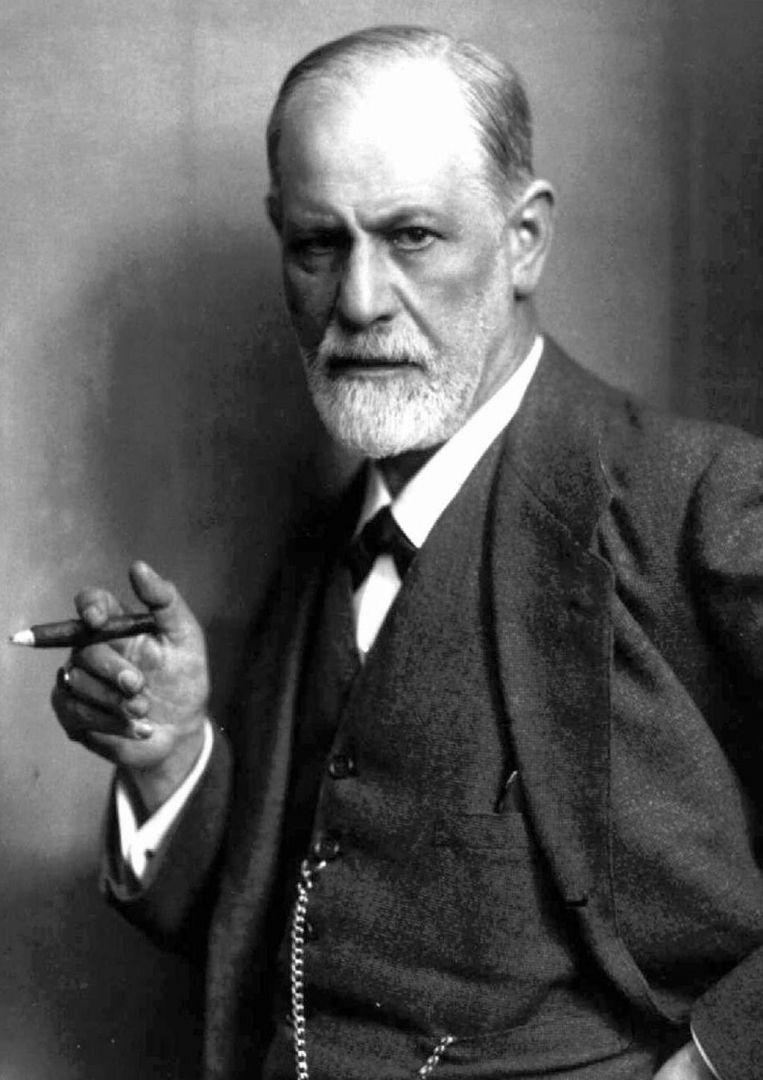

Sometimes a Cigar Is Just a Cigar

If, in your mind, you picked it up and toyed with it, smelled it, cut the end off it and lit it up, does that mean you were playing with a penis, or just that you craved a good smoke? Read More

Traditional Instruction?

When was the last time you sat in a classroom? For me, it was just a few months ago, when I went to a parent meeting with my daughter’s teacher. I noticed that the desks were arranged in pods of six, rather than in rows. Read More

Developing Knowledge

How do you develop knowledge?

Have you thought about it? The question is not how you learn, but how you develop knowledge. Perhaps it would be best to start off understanding what knowledge is. Read More

A Place Called ba: Rene Descartes and Ikujiro Nonaka Meet, Part 2

Back in the 1990s, another original thinker, Ikujiro Nonaka, started to wonder about how organizations created knowledge. His key discovery was that organizations do not create knowledge; people do. Read More

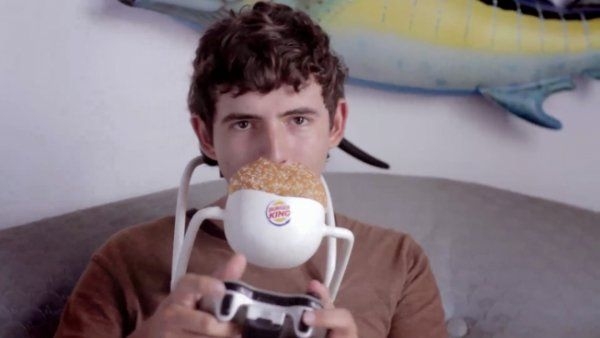

The Hands-Free Whopper of Cognition

Sometimes, just watching an idea in action teaches us more than we could learn from reading books or in a classroom. The marketers of trade shows and of the state fair midway understand the power of demonstration. Read More

No One Told Me I Had to Be Bilingual...I Don't Speak XYZ Company, Inc.

When you start a new job there’s always a learning curve. There are new people, new policies, and new responsibilities—all of which take time to get to know and understand. Read More

A Place Called ba

Traditional twentieth-century management typically focused on three resources, land, capital, and labor. In the late 1950s Peter Drucker started to recognize knowledge as a resource, and on the growing breed of workers who focused on the development of knowledge, whom Drucker dubbed “knowledge workers.” Read More

Teaching to Think

Plato learned from Socrates, and Aristotle learned from both of them through Plato’s writings, and the writings of other philosophers before him. These thinkers discussed and contemplated more than the meaning of life; they thought about thinking, and teaching others to think. Read More

Domain Knowledge

A few years ago, a colleague spoke about the need to hire a specific person because they possessed domain knowledge. The situation involved managing a temperature-controlled fleet that made multiple stops to deliver and pick up freight. Read More

A Place Called ba: Rene Descartes and Ikujiro Nonaka Meet, and Nietzsche Joins the Party, Part 3

Nietzsche only got part of the formula right. Nonaka postulates that knowledge is really a cycle, moving from conscious to unconscious, and back again. Or rather, from the tacit to the explicit, and back to tacit again. Read More

Lecturing

Previously, I wrote about the rise of compulsory schooling, and the social and economic conditions behind the Common School Movement of the 1860s – 1900s. The Common School movement benefited from three converging social trends: Read More

What is the Genesis of Knowledge?

The concept of infinity, something with no beginning and no end, is abstract. How far does space go before it ends? No one knows; so it must be infinite. How small is the smallest particle? How large the largest object? Read More