Beyond Cost Models:

No Cost Rules

Carlene looked at me and said, “Why are we doing the model? It just makes sense to convert all Vendor Direct to the CDC option.”

That was a real change in her point of view. I sat looking at Carlene. She looked at me, her right index finger crooked under her nose, pressing back on her upper lip. This was the pose Carlene took when she was not sure what to do, or when she was just thinking.

“Without a model, people will believe that emotion drives the decision,” I said. “Without a model, if everything flows through distribution, the buyers will argue that distribution is taking away the buyer’s flexibility to make deals.”

Carlene looked at me again, finger to upper lip.

Carlene had invested quite a bit of her time and effort in this model. I realized that this was not as much a change in her point of view as it was a challenge to my arguments about what should and should not be in the model. She was no longer openly challenging my assertions that the depreciation costs should not be included; she was now passively resisting, and perhaps not so passively.

I got the sense that she was waiting for me to agree that we should chuck the model. I had no idea of her opinions, or of her motives. I wanted to assume that Carlene was inherently good, that she just wanted to build a fair model, but I would never be able to figure it out at that moment. If I said to chuck the model, people would be upset about the wasted effort, and it would undermine trust in the organization. Just skipping the model was not the right political choice, so I had to come up with a way to highlight how the other functions worked.

“There are times where it makes perfect sense to ship store-direct,” I said. “For example, when it costs more to move the product through a distribution operation, or when the store chews through truckloads of the product quickly and there is not a good distribution option. Consider studs, dimension lumber, or plywood. Latex paints are another example of an instance in which the vendor’s delivery program is operationally better than ours.”

“But those are judgment decisions based on observations, not on the numbers,” said Carlene. “The model has to be based on numbers.”

I did not think so. “There are product categories where we can decide what to do based on data that is in the system, or from characteristics that are beyond dispute. Does a single store move a truckload of a product in a specific period, like seven days? If so, then it should move direct. These are logical arguments made from the numbers.”

We talked through a series of different products that we both agreed should move as direct products, like sheetrock, insulation, storm windows, and other products for which the supplier used delivery and distribution methods and equipment for the specific handling characteristics of the product. Talking each of these out, we both wrote up the justification for each of them by default distribution method assignments.

Intrinsic Decisions

The logical assignment of different vendors based on handling and volume characteristics was the first step beyond using costs to make the decision in the sourcing model. After we incorporated that logic, we began to identify other cost functions in the model that could lead to faulty decisions. The sorting according to logical rules also opened the door to creating commodity-specific cost models that we developed in the future.

We started to write a descriptive memo of the model process and construction with that meeting. By clearly documenting the process, and documenting the reasons for the decisions we made, we removed much of the resistance to the model, and the associated doubts about the results.

Implementing these intrinsic logical decisions to the beginning of the process simplified the construction and modification of the model. Based on observable and quantifiable factors, like the cube or weight of the products, we could better assign handling, freight, and storage cost factors. We, in essence, broke the model down into commodity-specific components, using the specific costs related to the execution of the physical movement of the specific products, which supported the perception that the model was more accurate.

Generic Costs

Still, a number of other cost elements remained in the model. Labeled generic costs in the model, these costs included back office functions, such as invoice payment, receiving labor, price tickets costs, and systems costs.

I was uncomfortable with these cost factors. My industrial management training from school told me that they were real costs, and should apply in the model if we followed established practices. Still, these were all overhead costs. I started to question the wisdom of developing different allocations of overhead cost based on a different physical flow of goods through the distribution network.

In my training, traditional cost accounting looked at the cost activities in operations as direct and indirect costs. We can draw a sharp line between the product and the direct cost — the labor to make an item, for example. It is difficult to draw a sharp line to an indirect cost, like building, utilities, or insurance. The cost accountants call these indirect costs.

In the initial meeting about the model, I upset the inventory management group leader when I challenged the concept of charging the building and equipment depreciation in the model, since the costs still existed regardless of the path the individual product followed through the network. While it was important to develop the cost to make something, for what we intended to use the model for, much of the overhead did not matter.

I started to look at the cost components in the generic costs, and ask the question, “Does it really matter?” My answers started to surprise me. It wasn’t the answers themselves that were surprising, but the reactions people had to the logic.

The model Carlene and I developed addressed this issue for direct costs by developing specific cost models for different commodity categories. But other indirect costs, like invoice payment, if treated as an overhead cost, still required allocation.

Or did it?

The problem for allocation of a broad “on-cost” percentage to all distribution methods introduced the danger of one distribution path subsidizing another in the model. What troubled me was the unintended consequences of the outcome of the model, or the unintended uses of the model results. If somewhere down the line someone used the model to determine the selling price, the company could miss profitable pricing opportunities by pricing products too high against the competition. We knew that the buyers could make product stocking mix decisions using the model, so adding allocated costs could lead to the buyers making wrong decisions about sales mix.

The ABCs of Activity Based Costing

Activity based costing (ABC) is one form of cost accounting developed to address the problems of classic cost accounting. Traditionally, cost accountants arbitrarily add a percentage of expenses into the direct costs to include overheads. The problem rears its head as the percentages of overhead costs rise, and the technique becomes increasingly inaccurate because not all products equally create the indirect costs.

ABC appeared on the cost accounting horizon in the mid 1970s in manufacturing. Still not broadly accepted in manufacturing, ABC was under the radar in the retail world, which still worked off measures like GMROI (gross margin return on investment) as a performance and decision metric. Using ABC, the cost accountant identifies cause and effect relationships between activity and cost, and objectively assigns costs. Once the cost accountant has identified and quantified the costs, they attribute the cost factor to each product to the extent that the product uses the activity.

Activity based costing requires a substantial amount of work. The manager must not only identify all the activities involved in a process, they must develop ways to apportion the costs based on the amount of activity each product requires. While I had taken accounting classes in college, I’d focused on managerial accounting, and not to an extensive depth. As I researched ABC, I felt confident that it was not above my ability, but it could be beyond the scope of my duties. The more I researched, and the more I thought about the effort, the greater my concern that this cure could create more trouble, more unintended consequences downstream.

The Cost of Paying an Invoice

The cost to pay an invoice was one of the generic overhead costs in the model. As we worked over the defined methods of developing each of the cost factors, we realized that we should not treat invoice payment as a percentage. Invoice transaction count reduction was one of the benefits of moving a product line to RDC or CDC.

The model used the following formulas for each distribution path.

For store direct, on average, each store processed a vendor direct shipment every three weeks per vendor.

200 stores X (52 weeks / 3 weeks = 17 invoices) = 3,400 invoices paid.

For the RDC operations, each DC ordered once every four weeks per vendor:

5 RDC X (52 weeks / 4 weeks = 13 invoices) = 65 invoices paid.

If the supplier moved through the CDC, which ordered on a two-week cycle:

1 CDC X (52 weeks / 2 weeks = 26 invoices) = 26 invoices paid.

This made sense as far as the activity went. It appeared to be obvious that there was a huge advantage for either of the two DC methods, as far as the impact of the cost of an invoice.

So how much did it cost to process an invoice? Early in the model process, Carlene did an analysis to figure out the cost, and she created a short memo to document her analysis. I found her analysis in the documentation.

“The Accounts Payable department processed about 2.4 million invoice payments the year before. The department employed eight people, six clerks, a supervisor and the manager. The clerks earned $18 per hour, $37,440 per year each, $224,640 total payroll. The supervisor earned $43,000 in salary, and the manager $51,000 for a total payroll of $318,640. The labor cost per invoice was $0.132.

In materials, each invoice paid required one check, mailed. The cost to print a check, the envelope and postage was $0.51.

Check printing labor is $0.21 per check, per the MIS department.

The A/P department uses systems to process the payments. Per the Accounting Income Statement, the MIS allocation for the AP function is $524,251. Systems cost per invoice is $0.218.

The A/P department uses 1,160 square feet of office. Real estate says that the office rent is $21 per square foot. Total space cost is $24,360. Cost per invoice, $0.01."

There were more entries for supplies and other factors, each with a cost of less than a penny an invoice. My eyes traveled to the bottom of the memo where the costs stack totaled.

Labor $0.132

Materials $0.510

Check Printing $0.210

Systems $0.218

Office $0.010

Supplies $0.004

Utilities / Phones $0.007

TOTAL $1.091 Per Invoice

Call it a buck and a dime per invoice. The numbers added up. Considering the company paid over 2.4 million invoices, the total cost for the invoices was over $2.6 million. Not an insignificant number.

I started to think about this effort from a different direction. Eight people in the A/P department paid 2.4 million invoices. I wondered about the time per invoice. Eight people times 2,080 paid hours equals 16,640 hours, or 998,400 minutes. 998,400 / 2.4 million = .416 minutes per invoice.

That did not make sense. Twenty-four seconds? It took me at least that long to open an envelope and pull the paper out. How could they pay a bill that fast? I had to go see this.

The Reality in AP

I took a walk up to the fifth floor to visit the A/P department. There were eight cubicles. Six were empty. Not “empty”as in nobody at their desk, but truly empty — nobody worked in the cubes. I walked to the back of the aisle and found both the supervisor and the manager.

After introducing myself and explaining why I was there, I mentioned the empty cubes, thinking out loud that the department must be moving.

“Oh no, we used to have six clerks,” said the manager. “We actually had about 20 clerks two years ago. With the new A/P system that went live the department shrank. We thought that we would need only six clerks, but the system worked better than the plan, and the other six transferred to other parts of the accounting department, or to other departments in the company.”

“Who is paying the 2.4 million invoices?” I asked.

“The system does most of the work,” said the supervisor. “We now take care of the manual invoices, the ones where there is no PO in the system. The stores and DCs process their operations invoices with the on-line voucher system, so we seldom have to mess with those anymore. We just process the corporate office invoices now.”

The Costs Do Not Matter!

I thanked the supervisor and the manager for their time. As I walked back to my cubicle I remembered that the DC Administrator had complained about the new invoice process until she went through it the second week. After a month there was no way she would have gone back to the old paper process; she was all smiles about the new A/P process.

The cost of paying an invoice did not matter! Automation eliminated the expense. I thought about how the ABC method of cost accounting required so much effort in figuring out the apportioned costs. Carlene did that in her model, unaware that the process had changed!

On the way to my desk I stopped in the break room to get a drink, and decided to sit for a moment and think.

⦁ If ALL of the product moved from store direct distribution to distribution centers, the company would have fewer invoices to pay.

⦁ We had about 650 vendors in the direct programs. Each vendor created about 3,400 invoices to pay. I did the math on a napkin: 2.21 million invoices.

⦁ If those 650 vendors moved to a DC program, they would create only 65 invoices each, a total of 42,250 invoices.

⦁ 2.21 million invoices – 42,250 = 2.16 million invoices not paid.

⦁ Using the model cost: 2.16 million X $1.09 per invoice = $2.3 million of cost eliminated.

I looked at my notes. The math was right, but the analysis was so wrong.

We still had the systems, the rent, and a little payroll. The manager told me that the A/P system consolidated all the invoices to single checks mailed once a week, so we would mail only 33,800 checks. Except the company paid over half the vendors through a new electronic funds transfer program, so it was about 16,000 checks per year.

The real cost for invoice payment? What did it matter? The costs would not change because of the distribution method.

I walked back to my desk, thinking about how many other overhead costs in the model really did not matter. I started to think about how many actual activity costs really did not matter.

Thinking about what the AP supervisor said about the people in his department — they’d transferred to other parts of Accounting or to other departments at corporate. I am sure that somebody used labor reductions to justify the new AP system. But the company had not saved a dime, it had just moved people to other areas. I realized that the projected labor savings at the stores for moving from store direct to DC flow was a myth. Unless we fired the people in the stores, the labor cost remained. And no store manager was about to fire these employees.

I had to figure out how much additional flow through the DCs would have to happen before we needed more people. I knew from my own experience that we always looked like heroes when the volume was up, because we had more throughput volume to offset our costs. Just like the buildings and equipment, we had unused labor capacity. If the other DCs were like the one I worked at, they could suck up significant flow before having to add more employees.

It was at that moment I realized that the cost model was useless. Until our distribution centers hit capacity, we had to exploit them them for all the products the facilities could handle. The more I thought about it, the less any of the store-direct made sense, except for the products that Carlene and I had identified that the supplier could deliver better than we could.

I knew that Carlene would not believe me. I had to work with her, walking her through the logic point by point, letting her come to the same conclusion, to make her believe. I kept up my work with Carlene over the next few weeks, until she could see that the model was useless. Once convinced, she started to convince her boss, and others, that everything should flow through distribution, and the only question was which set of centers.

Epilogue

The model work that we started became an effort to develop the Total Landed Cost at Store, what people started calling Real Cost. Because of my work with the transportation and distribution group, I remained involved in the process, mostly working to convince people that most of what they wanted to tack onto the landed cost did not belong.

At some point Carlene left the company, and I lost an ally. I missed her razor-sharp ability to cut to the chase, the crooked index finger to the upper lip, and her flat Missouri accent when she called me “Sweet Pea.” Mostly I missed her ability to tell others that they did not know what they were talking about in a way that they accepted.

After another long meeting dealing with another fool who wanted to charge another overhead account to the Landed Cost, I vented to my Vice President, Jim Bryan, that the building was “filled with fools.” Laughing, Jim told me to take a walk outside in the sunshine and get some air. Jim was right, so I took that walk.

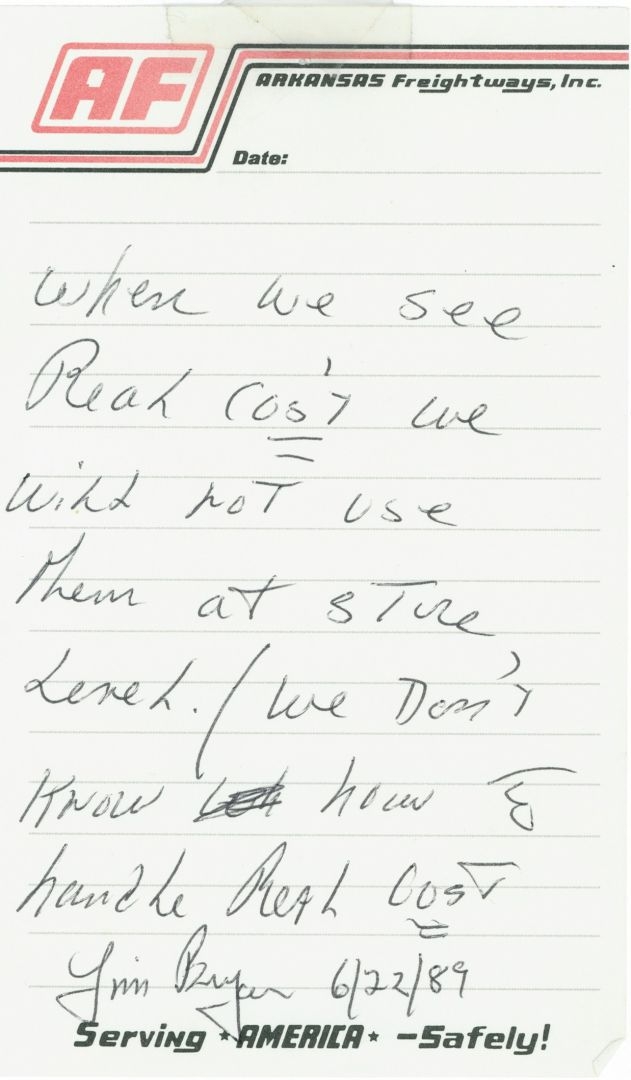

When I returned to my desk, I found a slip of note paper on the seat of my chair. Picking it up, I recognized the handwriting of my Vice President.

“When we see Real cost we will not use them at store level. / We don’t know how to handle Real Cost." - Jim Bryan 6/22/89

I pinned that note to my cubicle wall. It has traveled with me ever since, through several companies and jobs. It hangs on my corkboard today, true as it was so many years ago.