It's All in the Strands,

Yarns, and Fibers

There are times where the metaphor of the supply chain is wrong. I think that a rope or a system of pipes is more accurate.

Consider the construction of a rope. Look closely. There are thousands of fibers in a rope, which are bound together into yarns, gathered into strands and braided together into a single line. The strands give the rope the flexibility to bend and stretch. Without that flexibility the rope would not be as useful — we could not tie knots with it, and it would not hang loosely when we throw it over the side of a cliff to climb on it. The strands give the rope resilience to absorb shock as we rappel. The multiple strands make the rope stronger, the braiding lending it greater tensile strength than the sum of the strength of the strands.

Our inbound supply chain is like the fibers, yarns, and strands of a rope — they come together at the distribution center or factory, blended together into lines that spread back out to the stores and customers our operations feed. Just as it is important for the yarns to freely flow into a rope machine at the right place, our inbound supply yarns and strands must flow into our operations at the right time to perform the operations and meet the customers' quality expectations.

Think of the structure this way:

- The individual SKUs (products) are the fibers.

- Shipments are the yarn from the vendor.

- Our factories and distribution centers construct the strands.

Simple Solutions in a Complex Network

The inbound supply flow into a factory or distribution center is a complex network of paths, through which material flows. Each supplier represents a different node, and the transportation to the customer a different thread. A demand signal from the customer, a purchase order, starts the fulfillment process at the supplier’s end of the thread. The supplier then ships the materials to the customer.

Many factors influence the decision to purchase a product from a supplier. While most procurement managers and buyers like to think that they make the best overall deal for a company, the process they follow often overlooks considerations like lead time and performance variability. Traditionally, the key decision points have focused on the quality of the material, the price, and whether the supplier could fulfill the general demand. Rarely does the buyer or procurement manager pay attention to the timing and costs of the execution process. Why? Perhaps because these process managers are not trained to think about execution issues, or they consider execution issues unimportant to the decision of who to buy from. Some buyers do pay attention to these issues, but most do not.

It is important to consider the details — the strands of the inbound flow — to improve execution performance. If you want to improve the overall performance of the flow while reducing lead time and variability of performance, you must examine the detail processes, measure the performance of each of the strands, and then apply specific, simple solutions to each strand as needed. As one inventory manager lamented to me a few weeks ago, that detail examination is a daunting task, because a retailer could have over 10,000 suppliers and multiple distribution centers. In her case, multiplying the combinations creates over 60,000 strands to examine, to measure, and to manage. It becomes too big a problem for most people to fathom. But if a company wants to create a high-performance supply chain, the managers must address the detail of the strands by developing ways to measure, examine, and improve the performance of each of the strands.

Again, most supply managers lose sight of the forest because of the number of trees. They have to be able to step back. Let’s consider an example of a network decision as a starting point of understanding.

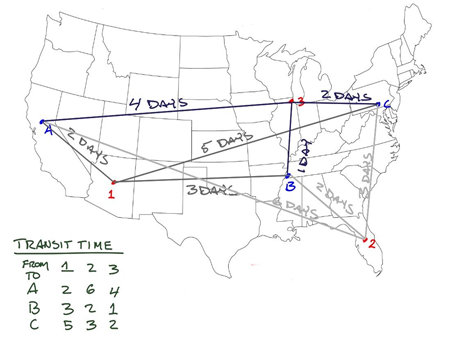

Using apparent distance as a proxy for lead time, the initial tendency of many supply-chain managers — assuming the key variables of quality and price remain constant — is to select the closest vendor to supply the demand. The vendor in Phoenix supplies Stockton, and the Chicago vendor supplies Memphis and Carlyle. The vendor in Orlando misses our business.

In the old days of logistics, managers used a rule of thumb of one day of transit time for each 500 miles of distance. As a rule of thumb the idea still holds — as a simple proxy. The reality is that even 20 years ago the 500-miles-per-day rule did not hold for areas known for traffic congestion. Today, the 500 miles/day rule is less accurate, considering the different transport options now available, how LTL carriers have developed faster classes of service (for a higher rate), how regional carriers offer faster service than national carriers, truckload teams, improved intermodal services, and a host of other options. To better figure out our options, we can’t rely on proximity on the map; we need the actual data.

We ask the respective vendors to tell us what transit service they can provide using their carriers, and then chart the data on our map. It appears that our initial assumption holds. Using the vendor in Phoenix to ship to Stockton and Chicago to serve Memphis and Carlyle, all our distribution centers get service in two days or less.

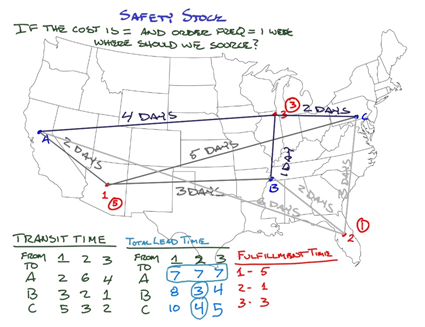

But we only asked for the transit time, not the total lead time. Total lead time is a combination of the vendor’s fulfillment time, how long it takes the vendor to process and ship our order from the time they receive our purchase order, and the transit time. Our map is incomplete, and therefore so is the analysis.

We go back to the vendors and ask for the fulfillment time, and then look at our data again. What a change! The vendor in Phoenix takes five days to fill the order, while the Chicago vendor takes three days and the Orlando vendor takes only one day. In fact, the Orlando vendor says if the order is in before 2:00 PM they will ship on the same day!

Because of the Phoenix vendor’s performance, the lead time into Stockton is seven days from all three vendors. Orlando’s rapid fulfillment shifts the Memphis and Carlyle decisions away from Chicago.

We pay attention to the lead time because it is a critical input to safety stock calculations and reorder point timing. We assume that there will be less variance in performance. With a shorter lead time, we can time reorders closer to the lowest point we want to drive our inventory, using rapid replenishment to help increase turns.

Let’s pretend we are the decision maker. We make the deal and select Orlando as our supplier for the Eastern centers and Phoenix for Stockton.

Next, we jump ahead a few months and look at the actual execution.