Closing the Hathaway Man

This weekend I received a note from a fellow traveling along the advisor and consultant trail. He lamented the fact that 98.756329817 percent of his clients invest more effort into defeating his counsel so that they can justify termination of the profit-destroying fees they pay than they do into the mission of getting their performance right.

Profit-destroying fees? His clients established that the fees they paid my colleague came straight off their bottom line, ensuring that they could not be as profitable as companies that didn’t waste their precious money on expert services.

The note reminded me of the story behind the story of the Hathaway Man shirt campaign of the 1950s–1970s.

The Front Story

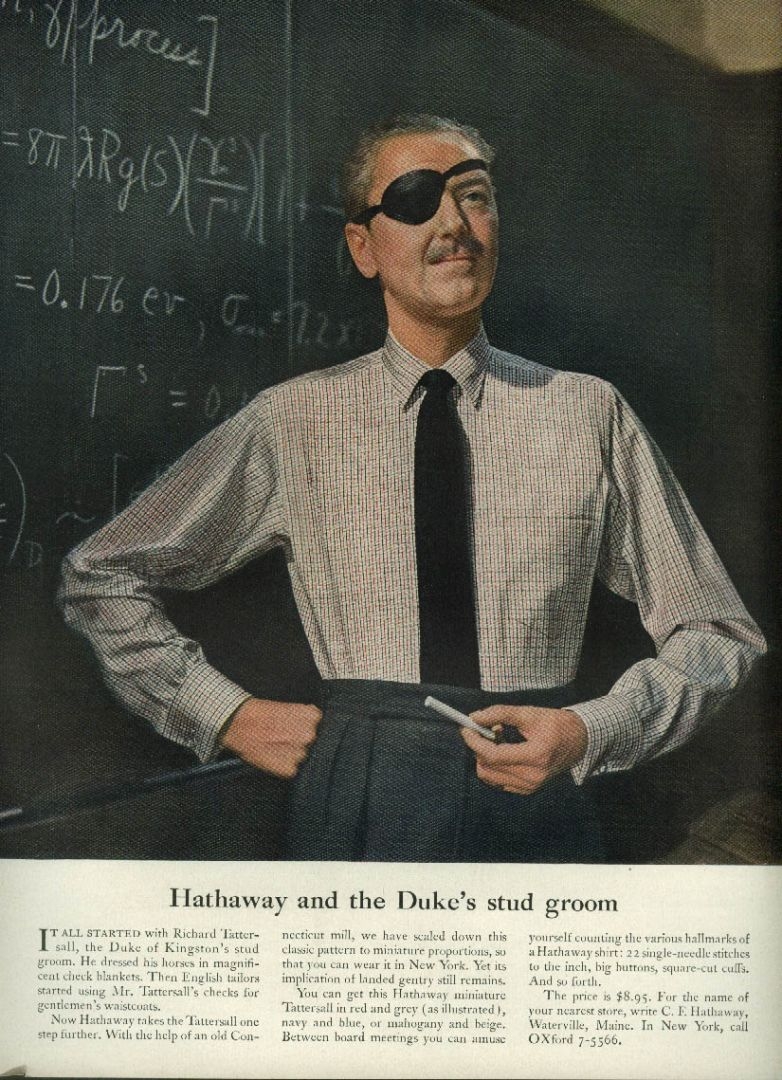

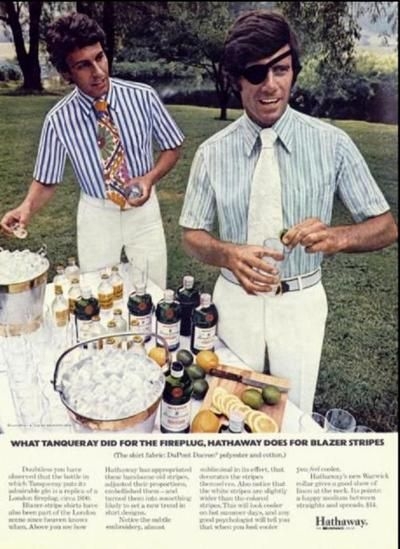

The story is about how one of the Madison Avenue greats, David Ogilvy of the Ogilvy & Mather ad agency, decided on the way to a photo shoot to buy a few cheap eye patches. Ogilvy arrived and asked the model and photographer to shoot some shots with the eye patch, just to humor him. When Ogilvy saw the resulting photos, he realized he had just the right images to capture the reader's imagination and draw him into the picture; the reader would wonder what this gentleman had done that made it necessary for him to wear an eye patch. The reader would then read the headline, which was designed to be intriguing. The headline of the copy always contained the word Hathaway, and talked about the shirt in a way that compelled the reader to dive into the copy.

The story is about how one of the Madison Avenue greats, David Ogilvy of the Ogilvy & Mather ad agency, decided on the way to a photo shoot to buy a few cheap eye patches. Ogilvy arrived and asked the model and photographer to shoot some shots with the eye patch, just to humor him. When Ogilvy saw the resulting photos, he realized he had just the right images to capture the reader's imagination and draw him into the picture; the reader would wonder what this gentleman had done that made it necessary for him to wear an eye patch. The reader would then read the headline, which was designed to be intriguing. The headline of the copy always contained the word Hathaway, and talked about the shirt in a way that compelled the reader to dive into the copy.

This man carried an air of sophistication, intelligence, and leadership. He was always in charge and relaxed. He never worried about his shirt. He may have looked a little highbrow, somewhat smarter than the average person, perhaps a member of the richer class, an aristocratic man with a romantic life.

The model who appeared in the Hathaway Man ads was Baron George Wrangell, a real Russian aristocrat. The Baron had two functioning eyes and perfect vision, so the eye patch was just a prop. Wrangell always looked a little stiff in the 1950s' ads, probably because of the apparatus required to hold his hands steady—they tended to shake during photo shoots, on account of his drinking.

The brilliant copy was always spot on, highlighting the construction of the shirt, the subdued stripes that did not clash with the suit or tie, how the drip-dry cloth saved time, and how the full cut of the shirt provided room for the man on the go to move. The copy never told you why this man wore an eye patch, but it told you everything about the shirt he was wearing.

The $3,176 ad campaign (big dollars in that time) was a huge success. The first time the ads appeared in "The New Yorker," all the stores that carried Hathaway shirts sold out within the week. This campaign lofted the sleepy little 100-year-old regional CF Hathaway company of Maine from a small unknown maker of shirts and uniforms into a major brand.

The Story Behind the Story

The real genius of this story is not David Ogilvy. The true inspired genius of the story is Ellerton Jette (right), the president of the Waterville, Maine shirt maker. Jette did not have much money, but he wanted to turn his company into a major brand. Jette knew that if he could get the advertising power of Ogilvy& Mather behind the campaign, even with a micro budget of $30,000 to start the launch, Hathaway could quickly rise to national brand status.

The real genius of this story is not David Ogilvy. The true inspired genius of the story is Ellerton Jette (right), the president of the Waterville, Maine shirt maker. Jette did not have much money, but he wanted to turn his company into a major brand. Jette knew that if he could get the advertising power of Ogilvy& Mather behind the campaign, even with a micro budget of $30,000 to start the launch, Hathaway could quickly rise to national brand status.

The trick was to get Ogilvy & Mather, which was already a huge agency, to take on the assignment for a meager $30,000. So Jette devised a simple compelling pitch that would close Ogilvy.

“I have an advertising budget of only $30,000,” Jette told Ogilvy. “And I know that’s much less than what you normally work with. But I believe you can make me into a big client of yours if you take on the job. If you do take on the job, Mr. Ogilvy, I promise you this: No matter how big my company gets, I will never fire you. And I will never change a word of your copy.”

Jette knew the paltry $3,000 that Ogilvy would have made from the job would not motivate the Madison Avenue powerhouse. Jette therefore looked for ways to solve the real problems that Ogilvy and every other Madison Ave exec faced. First, no matter how good Ogilvy was, clients always eventually walked to the next shop across the street. Second, clients always wanted to mess with the copy in the advertisement. By making those two promises, never to fire the agency and never to change the copy, Jette made himself irresistible as a client. Jette convinced Ogilvy that he trusted Ogilvy’s marketing expertise and that he would remain loyal to Ogilvy as a reward for continued success.

Jette sold Ogilvy by providing solutions to Ogilvy’s problems. This earned Jette the support of perhaps the strongest print-image marketer of the 1950s, exactly what Jette needed to turn Hathaway from a little Waterville shirt maker into the major brand it was to become. Jette remained faithful to Ogilvy and his firm for as long as he owned CF Hathaway. While he sold it to Warnaco in 1960, the company remained faithful to his promise (no doubt because Jette was still chairman of the board).

Jette sold Ogilvy by providing solutions to Ogilvy’s problems. This earned Jette the support of perhaps the strongest print-image marketer of the 1950s, exactly what Jette needed to turn Hathaway from a little Waterville shirt maker into the major brand it was to become. Jette remained faithful to Ogilvy and his firm for as long as he owned CF Hathaway. While he sold it to Warnaco in 1960, the company remained faithful to his promise (no doubt because Jette was still chairman of the board).

Eventually Warnaco switched agencies, moving the Hathaway account in 1983 to Eric Mower & Associates, and later to TBWA/Chiat/Day, and eventually doing its advertising in-house. By the time of the move, times had changed, Ogilvy had retired, and advertising had moved from print to television. Hathaway finally closed in 2002, the second-to-last US-based shirt maker, and the oldest remaining shirt maker in the US.

Hathaway did not close because the marketing and advertising environment had changed. It died because the company could not compete on price with Asian shirt makers. However, Hathaway became the number one men’s dress shirt maker in the world as a result of Ogilvy's advertising. For 113 years before that meeting, CF Hathaway was just a small shirt maker in Waterville, Maine. After that meeting, the company’s revenues and profits skyrocketed. Jette trusted Ogilvy to make his company's shirts more than attractive; he trusted Ogilvy to make them desired. Jette trusted Ogilvy to convince men that they wanted to be like the Hathaway Man.

Why This Story Matters

How many times have you failed to take a mentor’s advice?

I shudder to think of the piles of money that clients have wasted because they did not listen to what I told them would happen if they continued down the path they were on.

Not long ago, I worked with a client who agreed that the plan I put together with his team was the right thing to do. He could see the logic, and it made perfect sense to him. He even said it made perfect sense.

Two weeks later, he decided to do something that destroyed that plan. The destruction was massive. It was so bad that a few months later the client was forced to let people go, and to reduce the size of the business and the scope of services he needed from outside parties, including me. His argument: my fees came straight off of their bottom line. He then attempted to place the blame for the disaster at my feet, claiming I had not made it clear enough that if he acted as he did, the result would be a catastrophe.

He was right. I did not make it painfully clear that his actions would bring his company to ruin. I did not chain him to his chair and confiscate his computer and his smart phone to prevent him from issuing the instructions that devastated his company.

Too bad he wasn’t like Ellerton Jette.