Big Data, Or Big Headache?

The promise of big data is that we can make more data-driven decisions. The promise is also the headache, because big data also means that there is more data for us to consider when making those decisions. More data, more complexity. More complexity, more chances that we make the wrong decision because we choose the wrong data to make our decision.

I hear sometimes from clients and supply chain pundits that the work has become more complex because the world is more complex. I don’t agree. The world is just as complex today as it was a decade ago. The work is more complex because of the way we have decided to conduct the work, not because the world is more complex.

Are We More Complex?

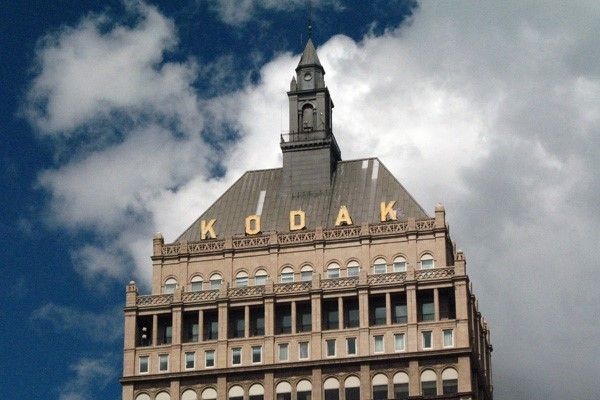

Consider the change in supply chain management from the 1980s to the present. Supply chains of the 1980s, in the broad sense of the word, were vertically integrated. If you bought a roll of Kodak film in 1981, almost all of the content of that roll of film came from some part of Eastman Kodak. The film stock, the emulsion, and silver halide all came from an Eastman Chemicals plant. In a Kodak film plant, employees of Eastman Kodak used Kodak assets to spread the Eastman Chemicals emulsion across plastic film made by Eastman Plastics. The machines rolled the film into metal and plastic canisters made in a Kodak plant. The cardboard boxes? Kodak. The printing on the boxes was done on presses in a Kodak plant. The trucks that delivered the film? Yeah, they said Kodak on the sides.

Consider the change in supply chain management from the 1980s to the present. Supply chains of the 1980s, in the broad sense of the word, were vertically integrated. If you bought a roll of Kodak film in 1981, almost all of the content of that roll of film came from some part of Eastman Kodak. The film stock, the emulsion, and silver halide all came from an Eastman Chemicals plant. In a Kodak film plant, employees of Eastman Kodak used Kodak assets to spread the Eastman Chemicals emulsion across plastic film made by Eastman Plastics. The machines rolled the film into metal and plastic canisters made in a Kodak plant. The cardboard boxes? Kodak. The printing on the boxes was done on presses in a Kodak plant. The trucks that delivered the film? Yeah, they said Kodak on the sides.

When all the parts of a supply chain belong to the same parent organization, managing the different parts is easy because there is a natural alignment of purpose. Eastman Chemical existed to supply Eastman Kodak with the chemicals needed to make Kodak films. Eastman Chemical may have sold some chemicals on the side to make more profit from the byproducts of the chemical process, but that revenue was just a bonus. If the film division needed more film stock, Eastman Chemicals made the materials. As demand rose for processing, they made more chemicals for film and paper processing.

But what happens if demand drops and there is excess capacity? With only one customer, Eastman Chemical depended on the demand from its parent company. Excess capacity meant underutilized assets and resources. The financial engineers of the era looked at these vertically integrated assets and saw a problem. They applied their DuPont Formulas and determined that the return on assets was not as strong as putting the same cash value to work in other investments. Strategic consulting practices like BCG and Bain started to point out that companies needed to focus on parts of their businesses that made more profit, and unload the parts of those businesses that were nothing but costs.

The great wave of outsourcing started in the 1980s, as the financial teams of the great conglomerates searched for ways to innovate more value out of the assets that these massive companies had collected in the 1960s and 1970s. Companies sold off whole divisions and outsourced the supply of materials to other companies — sometimes the same companies that had bought the old plants and equipment.

By the end of the 1980s, Eastman Kodak had changed. Eastman Chemicals had become a freestanding chemical company that had to compete in the market. Eastman Plastics disappeared. Eastman Kodak now bought film, emulsion, packaging, and labels from a variety of suppliers. Some of those suppliers had once been Kodak companies, but now not only competed for Kodak’s business, but competed for the printing and packaging business of other customers.

With that sell-off, the art of managing the supply chain became more difficult. Eastman Chemicals now needed to make a profit selling film stock, emulsion, and processing chemicals to Kodak. Facing pressure from competition like Fuji, Kodak needed to lower costs for film and processing materials. The costs of the chemicals supplied by Eastman Chemical increased to the point that Kodak had to look to Eastman Chemical’s competitors to get lower-cost materials. As Kodak changed sourcing, Eastman Chemical had to start looking for other customers, and finding no other demand, innovated and changed to make other chemicals that created better margins.

So much change with so much added complexity. What really changed? What was the cause?

What Changed?

The data used to make decisions changed. So did the questions that leaders asked.

In the vertically integrated company, what mattered at the end of the reporting period was the cash and profit the entire company generated. Internal managerial accounting may examine the operations costs and return on asset of the different operating divisions, but the divisional performance looked into the corporate performance of the corporation. What investors of the period wanted to see was the performance of the corporation; that is, whether it made enough money to pay for growth and pay dividends. It did not matter if an individual division did not make a profit itself as long as the materials made by that division lowered material costs so the entire corporation made more profit.

As the cost of computer systems dropped, and more companies invested in mainframes and mini computers, the amount of data increased. New management systems like manufacturing resource planning (MRP) and manufacturing process control systems (MPC) started to appear, so companies invested in these systems to look more closely at a more detailed level of data. Managers started to look more at reports and less at the floor.

The new data introduced new tools, new measures, and a new focus. Some of these measures already existed, but required manual effort to collate the data. The new systems collated the data faster, did the math, and spit out reports on paper. Data-processing professionals — what IT people of the day were called — developed new reports and programs that created new ratios.

Managers in the 1980s saw more data in a month than their predecessors saw in an entire year. It was not just the volume of the data; the velocity of the data increased too. The pace of decision making increased.

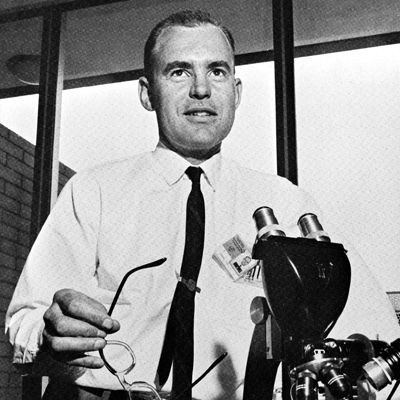

Intel co-founder Gordon Moore described a trend in a 1965 paper in which he noted that the number of components in integrated circuits had doubled every year since the invention of the integrated circuit in 1958. This observation became what we know as Moore's law, which states that computing power doubles in performance every 18 months.

Intel co-founder Gordon Moore described a trend in a 1965 paper in which he noted that the number of components in integrated circuits had doubled every year since the invention of the integrated circuit in 1958. This observation became what we know as Moore's law, which states that computing power doubles in performance every 18 months.

Moore’s Law does not just apply to the speed of processing power, or the amount of data a memory chip can store. Moore’s Law on steroids is the combination of the speed of processing power and the memory storage. What is X squared TIMES X squared? X to the fourth. The potential velocity of data quintuples as both the power of the processors and the ability of the memory double.

Brain Upgrade Anybody?

Don Benson, a pioneer in the development of advanced warehouse management systems, talks about the ability of managers to understand and use the information that the modern WMS can provide. He says the challenge is the “upgrades to the wet-wear” needed by managers to use the expanded functions of their systems.

The rate of change is increasing. Understanding what the information means requires higher cognitive function, the ability to understand the difference between causation and correlation, in order to convert sentiment into a data variable.

Upgrading our brains is not an easy task. More data tends not to help. More data tends to create more headaches.